You may have noticed on a recent flight a small, not-so-subtle advertisement for Southwest.com, WestJet.com or Ryanair. The ad is on the upward sloping mini-wing on the tip of the wing, called a winglet. The tips of airplane wings are adorned with all manner of winglets, sometimes featuring a distinct curve, like the Airbus A350 or Boeing 787. Passenger jets without winglets, in fact, are becoming increasingly rare.

While the concept of winglets has been around since the early days of aviation, NASA researchers are credited with kickstarting the winglet craze. Dr. Richard Whitcomb, an aerospace engineer at NASA Langley Research Center, tested winglets — vertical airfoils on the tips of wings — compared to longer wings in a wind tunnel. Whitcomb showed that the winglets would improve cruising efficiency by 6-9%; tests by the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center using a military version of the Boeing 707 showed an increase in mileage of 6.5% for the same amount of fuel.

The next phase in development and use of winglets on commercial aircraft came courtesy of Aviation Partners, a Seattle-based firm that developed the first blended winglet (described below) for a Gulfstream jet.

How do Winglets Work?

Making sense of winglets starts with an understanding of the wing. The wing shape generates lift by exerting downward pressure on the air mass it is traveling through, causing a pressure difference below the wing compared to above; there is less pressure on the upper surface of the wing and more on the lower surface.

An Avianca Airbus A321 and a Delta Boeing 737-900ER at Miami airport in 2016, sporting two different types of winglet (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

From this pressure difference, the air below the wings rolls up and wraps around the top of the wing, causing a whirlwind named a wingtip vortex. According to NASA, “The effect of these vortices is increased drag and reduced lift that results in less flight efficiency and higher fuel costs.”

Winglets themselves are mini-wings, not unlike a sail. Winglets produce “lift” as well, but because they are tilted upwards, that lift results in forward movement inside the vortex and reduces the strength of that vortex. “Weaker vortices mean less drag at the wingtips and lift is restored,” NASA explains.

There is a caveat: Winglets also add weight — some 500 pounds each — and drag. However, the aerodynamic benefits outweigh the additional weight and drag. That’s why most jetliners made today come from the factory with winglets. For older aircraft, it’s up to the airline to decide whether it makes economic sense to add them, given the cost of installation and the expected fuel savings over the life of the aircraft.

Aviation Partners Boeing, a joint venture between Aviation Partners and Boeing, lists prices of around $1,000,000 for the retrofit of a Boeing 737. That’s a lot of money, but in an industry where fuel efficiencies are key, this is a capital expense that will pay off over the medium to long haul. For example, the company says that adding winglets on a Boeing 737-900 can save up to 150,000 gallons of fuel per year. With jet fuel prices currently around $1.90 a gallon, winglets would save $285,000 a year.

The Types of Winglets You Can See

Not all winglets are created equal. Even a casual look at the airplanes at any given airport will tell you that they can look very different from one another, from the small arrow-like wingtips found on some Airbus jets to the huge, upturned winglets of the Boeing 767, resembling the dorsal fin of an orca.

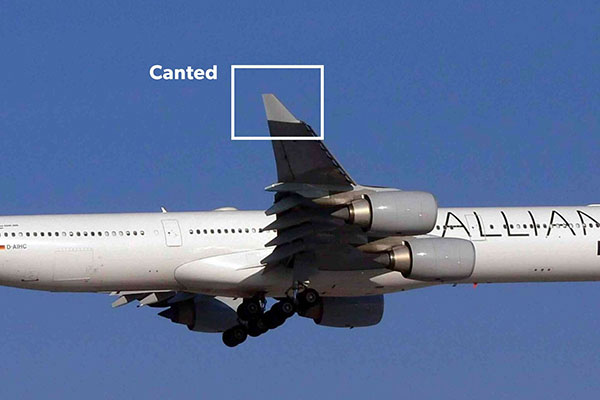

Canted winglets

Canted winglets are short, upward-sloping wedges; they can be found on Airbus A330 and A340 aircraft and on the Boeing 747-400.

Canted winglets on a Lufthansa A340-600 (Photo by JOKER/Hady Khandani/ullstein bild via Getty Images, modified by author)

These winglets are likely to disappear from view as the current models of the A330 go out of production and new wing shapes are developed. (The A340 and 747-400 are no longer made.) For example, the A330neo, which entered service last year, has smaller, upturned wingtips. (More on those below.)

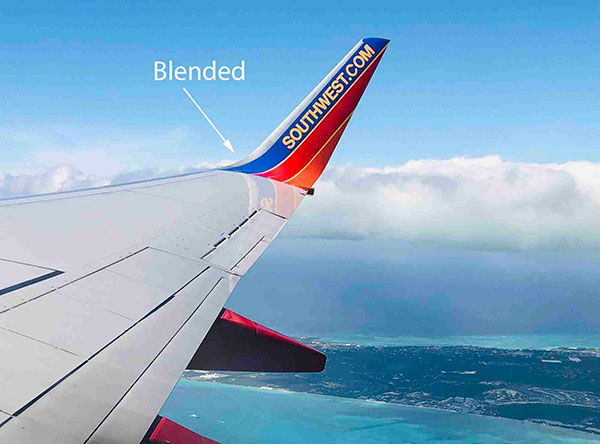

Blended winglets

You’ll find blended winglets on many models of the Boeing 737, the best-selling jetliner in the world. Southwest and Ryanair are the biggest operators, and you’ll often see them in North America at the tip of 737 wings with WestJet, Delta and American.

They are called blended winglets because they feature a much smoother transition from the wing itself to the winglet, which produces additional efficiencies compared to a canted winglet or wingtip fence (discussed below).

Photo by Jennifer Yellin/The Points Guy, modified by the author

Those are also the winglets found on most Boeing 757s and 767s in service today. They were not installed originally when the planes left the factory, but have been retrofitted by most operators, including American, Delta and United. At 11 feet tall, the 767 winglets are a sight to behold, and the ones on 737s and 757s are just a bit shorter at 8 ft, 2 in.

The blended winglet on a Delta Boeing 767-300ER (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

Sharklets: The Airbus version of blended winglets

Confusingly for plane spotters, newer Airbus A320-family aircraft also sport blended winglets that look very similar to the winglets on the Boeing 737 — except they’re called sharklets. The name is simply a nice piece of marketing. The Airbus design was the subject of a years-long patent dispute between Aviation Partners Boeing and Airbus, with Airbus the loser; the European manufacturer paid out an undisclosed sum to APB.

Sharklets on a Scandinavian A320 (Image courtesy of SAS)

Older A320-family jets, of the A318 through A321 models, sport instead so-called wingtip fences, which are described below.

Wingtip fences: An Airbus innovation

A wingtip fence on an Airbus A320 aircraft. (Photo by aviation-images.com/Universal Images Group via Getty Images, modified by author)

The small winglets that you’ll see on many Airbus variants are called wingtip fences. This type of winglet was meant to address the wingtip vortices that originate from the bottom of the wing, and therefore have a physical barrier below and above the wing. Spotting them is an easy way to differentiate between a Boeing 737 and an Airbus A320 family aircraft.

The fences are found on A320 family jets, as well as the A380 (not that you’d need to look at the wingtip to recognize the biggest passenger plane in the world!) The fences first appeared on some of the planemaker’s 1980s-vintage jets: the A300-600 and the A310, which have almost disappeared from passenger service.

Split-scimitar winglets

A Boeing 737-700 retrofitted with split-scimitar winglets (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

Similar to wingtip fences in that they have a physical shape above and below the wing, you’ll find so-called split scimitar winglets on many Boeing 737 aircraft. They are either delivered with new airplanes, or retrofit by Aviation Partners Boeing; the former appears on Boeing 737-900ERs flown by Delta, and the latter on many United Airlines 737s. They are a cross between a blended winglet and the wingtip fence, essentially blended winglets with an added airfoil below the wing. Their curvaceous shape resembling a scimitar gives them their name.

Up close with United Airline’s split-scimitar winglet, designed and installed by Aviation Partners Boeing. (Image courtesy of United)

Winglets on the Boeing 737 MAX

The Boeing 737 MAX has winglets that look similar to the split-scimitar ones, but they are slightly different and come as standard equipment with every MAX. You can tell them apart because they lack the tapering tips of the split-scimitar winglets.

The split winglet on a Boeing 737 MAX. (Image courtesy of Boeing)

Boeing designed these winglets specifically for the Boeing 737 MAX. The company says it used “detailed design, surface materials and coatings that enable laminar — or smoother —airflow over the winglet.” It should be noted that the winglets have not played a part in the two fatal crashes that have led to the ongoing global grounding of the 737 MAX.

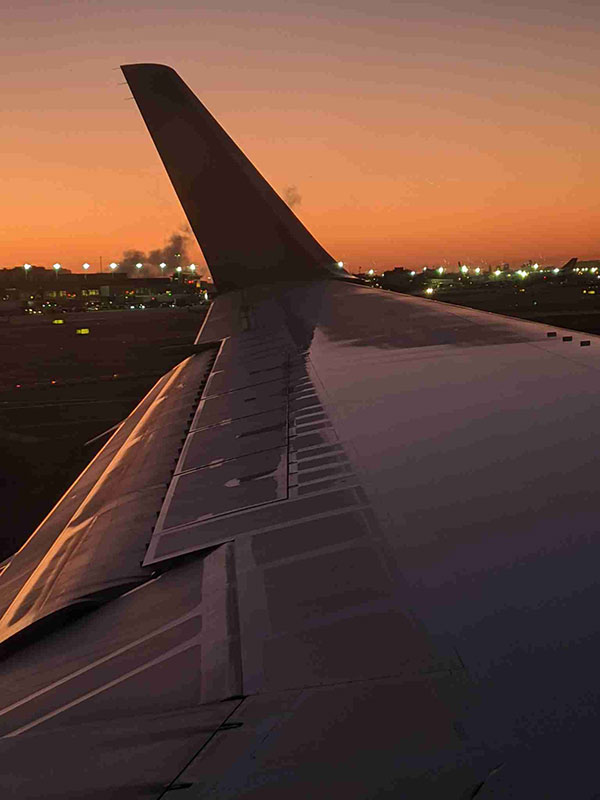

Raked Wingtips

A raked wing is not a winglet per se, but the tip of wing itself is swept back compared to the rest of the wing. The functionality is similar. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner, some Boeing 777s and the Boeing 747-8 all have raked wingtips, not winglets.

The blended winglet on a Delta Boeing 767-300ER (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

In the case of the 787, those raked wingtips also have a slight upward curve. So, why not install a blended winglet? In all likelihood, Boeing testing during the development of the wing indicated that the added weight of a traditional winglet did not outweigh the efficiencies gained by the wing design itself. In other words, they didn’t need it.

The wing of a Boeing 787 with its curved tip (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

The Airbus A350: What a shape!

The newest Airbus twin-aisle jet, the Airbus A350, sports distinctive, sinuous winglets, which Airbus also calls sharklets even though they don’t resemble shark fins as much as the A320’s. The Airbus design team sought a similar benefit — reduction of induced drag — by designing a beautiful, aerodynamically efficient shape at the outset. Unlike with the A320 family, these sharklets formed part of the design from day one.

A Delta Air Lines Airbus A350 with sharklet (Photo by Alberto Riva/The Points Guy)

The seamless integration of the A350′ sharklet into the wing is evident when looking at it from below.

The beauty of the wingtip of a Virgin Atlantic A350. (Image by the author)

A similar design is used on the A330neo, the newest version of Airbus’ workhorse widebody, flown by Delta among others. Combined with new, less fuel-thirsty engines, the new winglets help the A330neo fly nonstop 15% farther than the A330-300.

(Photo by A. Doumenjou/master films via Airbus)

Source: thepointsguy.com

Warning: Illegal string offset 'cookies' in /home/u623323914/domains/eng.bayviet.com.vn/public_html/wp-includes/comment-template.php on line 2564