Late spring and summer bring hot weather and with it, thunderstorm season in the US. If you’ve been delayed in your travels in the past month or so, you already know that. With some 40,000 thunderstorms annually around the world, pilots are dodging them daily. Here’s how they assess thunderstorm threats and adjust their flight plans accordingly.

Pilots call thunderstorms “CB,” which refers to cumulonimbus clouds.

According to the FAA’s weather guide for pilots, a thunderstorm is not an object, but more akin to a process that develops within cumulonimbus clouds. Those clouds start as the friendly, puffy white clouds you see on sunny summer days — cumulus clouds — with the addition of fast-rising moisture that turns into rain. (Cumulonimbus means heaping rain in Latin—a heaping rain cloud. Not so friendly.)

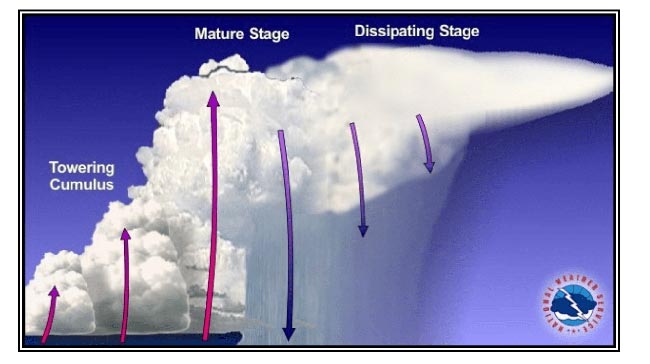

Thunderstorm development, from building stage to maturity and dissipation. (Image via FAA Weather Guide.)

Chris Brady, a longtime Boeing 737 and Airbus A320 pilot in Europe who runs the Boeing 737 Technical Site and Facebook Page, has seen his fair share of thunderstorms aloft — from a safe distance, of course.

“The moisture comes from the oceans or the land after rain,” he said. “You won’t be able to see the moisture at ground level, but as the day heats up and the air starts to rise, the moisture eventually condenses out, forming a cloud.”

In simple terms, thunderstorms occur when rising, humid air quickly and violently builds high into the sky. The air eventually cools to a point where the moisture condenses into rain. “Creating rain” releases heat, which makes the cloud grow even higher. Meanwhile, the falling rain leads to lightning and brings with it fast-moving, downward air as the rain falls. In a thunderstorm, there’s air moving upward and sideways very quickly — some 3,000 feet per minute — even as air is also being pulled down by the rain itself. It’s a nasty cycle. And that’s just a single thunderstorm cell; there can be multiple cells across long weather fronts stretching hundreds of miles.

Thunderstorms can be huge, from 30,000 feet to 60,000 feet high and as wide as 100 miles across. An airplane can’t fly over them—their service ceilings won’t allow for it. The FAA guidance is to avoid thunderstorms by at least 20 nautical miles, or 23 statute miles. And for good reason. Inside, the winds go in all directions, often violently. Plus, there’s a good chance of hail.

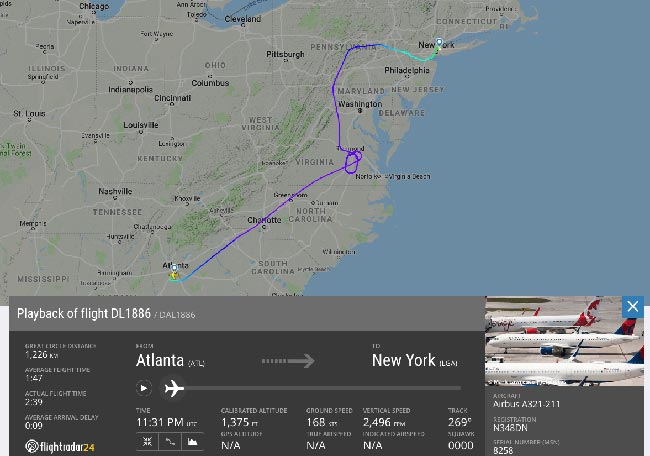

For example, see what the pilots of Delta Airlines flight 1886 did on July 7 on their route from Atlanta to New York: they held in a racetrack pattern over Virginia to wait for the storms over New York to clear, and then reached LaGuardia Airport with a long detour over Pennsylvania. That route took almost an hour longer than normal, but avoided flying the Airbus A321 through a violent summer storm.

Screenshot from Flightradar24.com

The issue with thunderstorms is not the lightning, except when that lightning is near the airport, causing a stop to ground operations. “Aircraft are designed to be able to withstand lightning strikes and every airliner gets struck, on average, six times a year,” Brady says.

“The fuselage acts like a Faraday cage, transmitting the lightning safely around the aircraft rather than through it, and generally, no damage is done.”

Preflight Preparation by Pilots

The incredible scale of convective activity. This image was shot by Chris Brady en route, capturing an aircraft safely skirting a thunderstorm cell.

“Most airlines don’t give their crew any advance warning of bad weather before they get to the airport. We as pilots just keep an eye on the regular TV or radio weather forecasts for that,” Brady said.

“When we report to the crew room before a flight we are given as much meteorological data as we need. This includes weather reports, forecasts, warnings, charts and satellite imagery,” Brady said. “From this data we will make a decision about the route we will fly and how much extra fuel we need to carry, both to pick our way around the storms and if necessary to hold or divert at the intended destination.”

What happens if thunderstorms are predicted on arrival at LAX for a flight departing New York? Does the aircraft still depart New York for Los Angeles?

“It depends upon each airline what their policy would be, but most would allow the flight to set off. The forecast is only a forecast and they can be wrong,” Brady said. “However, good practice would dictate, if there were CBs forecast at the destination, that you review the weather forecasts at the other airports nearby so that you have enough fuel to get to an airport which is not forecasting thunderstorms, in case yours is closed. Flying faster is an option but realistically we can only increase speed by a few percent so it doesn’t make that much of a difference.”

En-Route Technology

Brady explained that modern commercial aircraft have weather radar which superimposes weather information onto the map display for the pilots. The information comes from a radar antenna in the nose of the aircraft. The radar works by detecting water particles and displays different colors depending upon the density of water.

On this flight-deck display, Chris Brady’s Airbus A320 is a yellow cross in the center. CB cells are in red, and if you look closely, you’ll see lightning (zigzags) and hail (yellow triangles). Anything that is striped is below the aircraft, and solid colors are above the aircraft. (Image by Chris Brady.)

“Green is the lowest level and is OK to fly into. Amber is quite strong and should be avoided if possible. Red is the center of the [thunderstorm] and absolutely must be avoided,” Brady says.

Brady explained there are other elements on the screen that show turbulence, and newer displays show lightning and hail, as seen above. Brady recently navigated through a series of CBs, shown on the images below.

“We picked our way through, taking care to allow for the way the storms were moving by looking at the wind speed and direction shown in the top left corner of the screen. If you look at the left screen (the primary flight display) you can see that we were at 37,000ft and the tops of the CBs were still well above us,” he said.

Navigating CB activity. (Image by Chris Brady.)

“It was slightly turbulent, and in these conditions the speed increases and decreases in the moving air,” Brady explained. In the case above, the flight instruments showed that at the plane’s very high 37,000-foot altitude, there was a very thin margin, only 40 knots or 46 mph, between the stall speed — when the aircraft would be too slow to fly — and overspeed, which stresses the plane’s structure. So, trying to avoid those CB clouds by sipmly going above them would have been hazardous indeed.

“This is why you should never try to overfly a storm,” Brady said. “The speed variations can be considerable, and you could inadvertently stall into a storm.”

Mike Arnot is the founder of Boarding Pass NYC, a New York-based travel brand, and a private pilot.

Source: thepointsguy.com

Warning: Illegal string offset 'cookies' in /home/u623323914/domains/eng.bayviet.com.vn/public_html/wp-includes/comment-template.php on line 2564