Through the winter and well into the spring, Pacific extratropical cyclones move inland from the Pacific Ocean. They weaken as they cross the Rockies but then often regain strength on the Great Plains to cross the rest of the United States. Many dip to the south and then turn toward the northeast to travel along the Atlantic Coast before heading across the Atlantic Ocean. The whole package moves generally from west to east across North America, with changing weather hazards ranging from severe thunderstorms across the South to freezing rain or blizzards in the North. Aircraft icing can be a hazard anywhere in such storms.

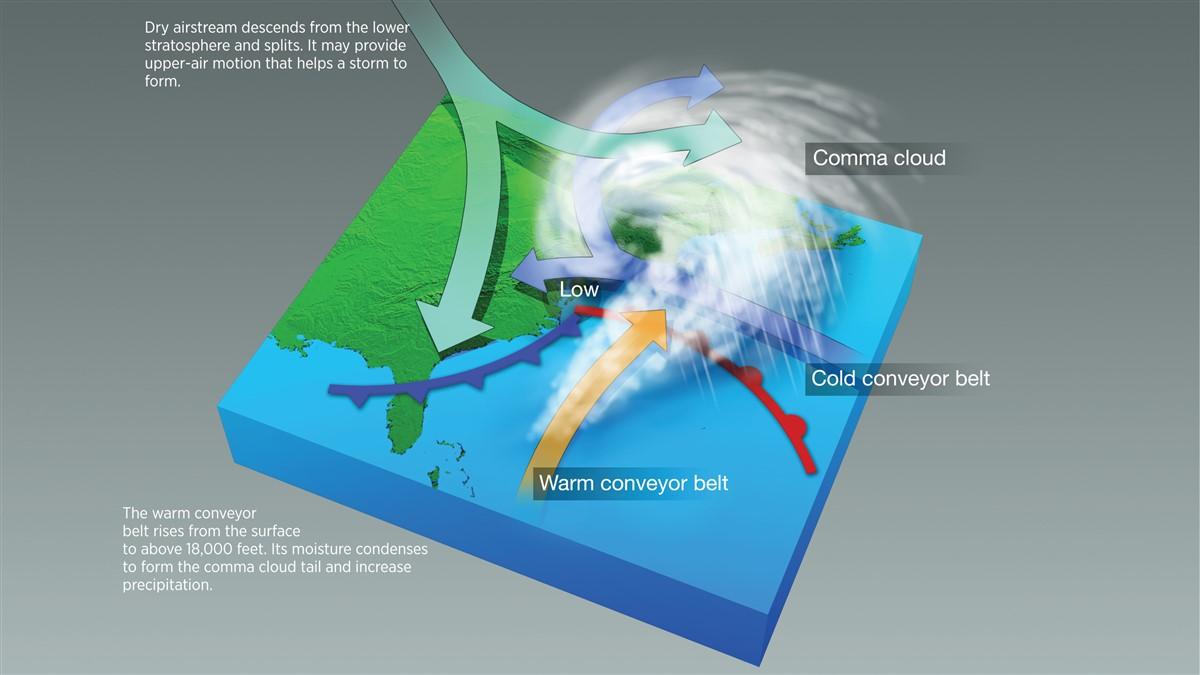

This three-dimensional look at what is going on inside many extratropical cyclones shows interactions among “conveyor belts” bringing in air from surrounding sources with varying air temperatures and combinations of water, water vapor, and ice.

The huge supply of relatively warm, humid air that the warm conveyor belt carries on the storm’s eastern side helps explain why nor’easters often dump heavy snow along the U.S. East Coast from the Carolinas to New England. Any pilot who happens to fly into this conveyor belt or in precipitation below it would find heavy ice forming on the airplane. This, of course, would not be the only icing found in the storm.

The March 1993 “storm of the century” extratropical cyclone dumped snow as far south as western Florida, with amounts ranging from 13 inches in Birmingham, Alabama, to 42 inches in Syracuse, New York. The storm closed airports as far west as the western Great Lakes and closed every major Eastern airport from Atlanta to New England, forcing U.S. airlines to cancel roughly 25 percent of all of their U.S. flights.

Cyclones

Extratropical versus tropical

A cyclone is a storm with winds flowing around a center of low atmospheric pressure—counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere, clockwise in the Southern. Cyclones can be roughly 60 to more than 150 miles across.

Tropical cyclones, such as hurricanes, form over ocean water that’s warmer than 89 degrees Fahrenheit and begin weakening and die when they move over colder water or land.

Extratropical cyclones form over land or cool ocean water. Temperature contrasts between large masses of warm and cold air supply their energy. They weaken and die when they move into regions with small temperature contrasts.

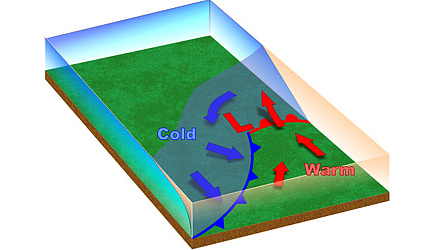

L: The low-pressure storm center surrounded by counterclockwise winds. Cold: A cold front where cold air is shoving under warm air. Warm: A warm front, where warm air is shoving over surface cold air.

Source: aopa.org

Warning: Illegal string offset 'cookies' in /home/u623323914/domains/eng.bayviet.com.vn/public_html/wp-includes/comment-template.php on line 2564