The world of agricultural aircraft is an unending source of weirdness. These aircraft are basically tractors with wings. But, even in this world of strange and stranger, some planes stand out.

These unusual machines include Fletcher FU-24s, Kensgaila VK-8s, and PZL M-15 Belphegors. It is though the aircraft have been designed with a single purpose: to laugh at Marcel Dassault’s well-known quote: “For a plane to fly well it has to be beautiful.”

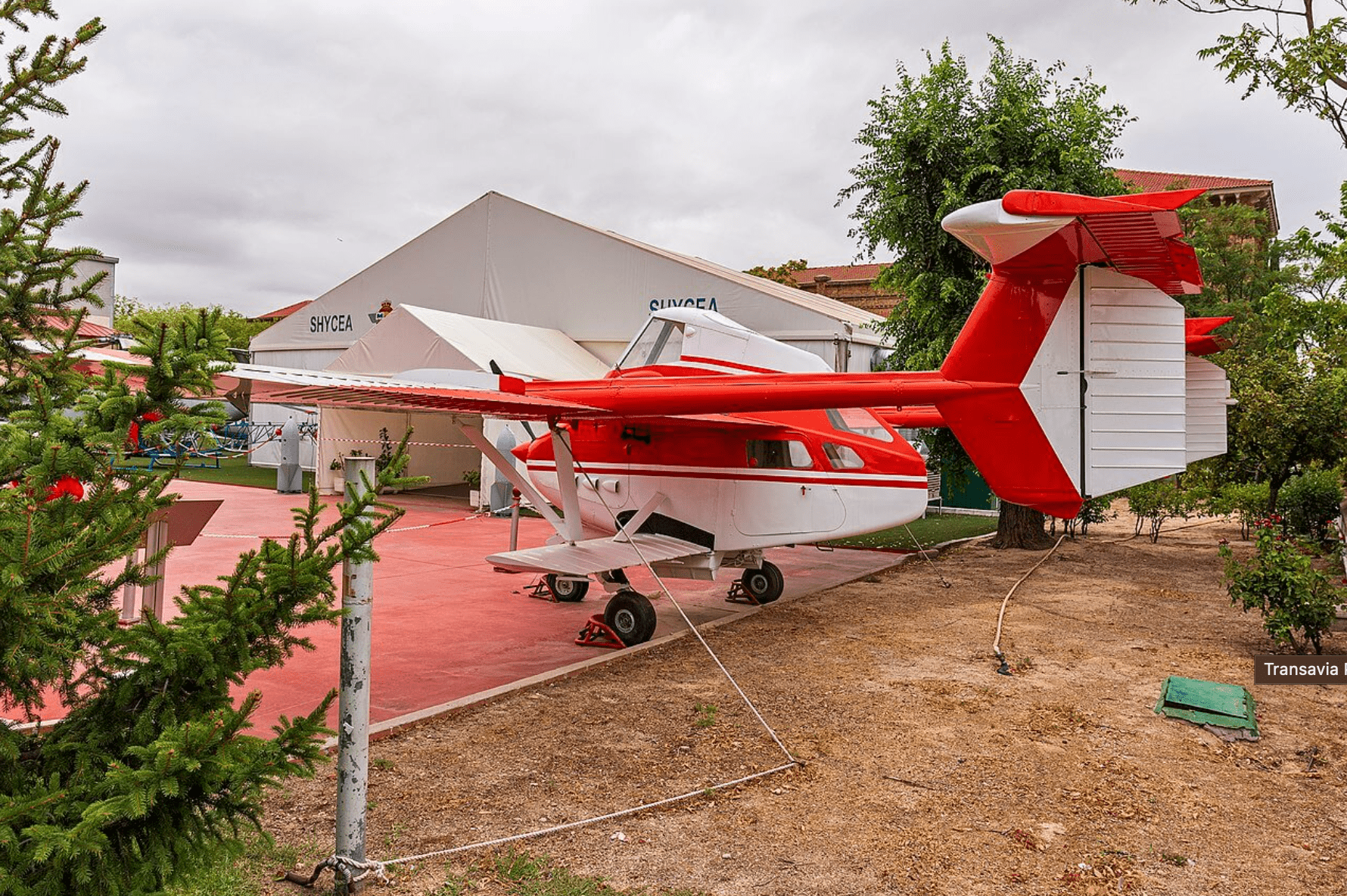

While not as well-known as the PZL M-15, the Transavia PL-12 Airtruk deserves a place in this eclectic company. Many descriptions emphasizing its weirdness are floating around the internet. Some say that the PL-12 looks like it was drawn by a child. Others claim that it was once a normal-looking aircraft that was reassembled after an unfortunate crash by a person who didn’t understand where each part was meant to go.

The real story behind PL-12’s inception may not be as odd as these descriptions, but it is certainly unusual. Unbeknown to many, it was a continuation of a longish line of agricultural aircraft, one stranger than the next, conceived by the person best known for designing flying cars.

A ‘barrel’ with wings

By the mid-1950s, Australia was in a clear need of agricultural airplanes. An aircraft maintenance company called Kingsford Smith Aviation Service took on the job of designing one, and brought in Luigi Pellarini, an Italian designer who became famous after creating one of the earliest flying cars, the PL-2.

The car was barely capable of flying and never took off commercially, yet the designer had a much better run with vehicles that didn’t have to combine two modes of transportation into one.

It is difficult to tell exactly what prompted Kingsford Smith Aviation Service to hire Pellarini for the job, but its gamble was somewhat successful. In 1956, the Kingsford Smith PL.7 took off from an airfield outside of Sydney. If contemporary accounts are to be believed, the aircraft was only expected to do a short hop, but the pilot found it so easy to control that he proceeded to climb for a bit and then do a loop around Bankstown suburb.

Kingsford Smith PL-7 (Image: aviastar.org)

PL.7 was essentially a barrel with a cheap engine and two pairs of wings welded on. In addition to the pilot, the ‘barrel’ had to hold fertilizer to be sprayed, so, to make it easily accessible, Pellarini got rid of a conventional tail and replaced it with two tail booms attached to the wings. This had an additional benefit in that the tail would not be bathed in fertilizer each time the aircraft did its job, thereby reducing corrosion and saving on maintenance costs.

Reportedly, the visibility from the cockpit was atrocious which made landing difficult because much of the aforementioned ‘barrel’ was sticking in front of the cockpit. There were ways to solve this problem, but the aircraft did not receive appropriate attention from would-be buyers, so the design never went beyond the prototype.

A kitbashed bomber

Pellarini was not content with failure and so he made another attempt. This time it was on the other side of the Tasmanian sea. New Zealand’s Bennet Aviation expressed an interest in the design, providing the Italian with funds to improve on his idea.

Thus, the Bennet PL.11 was born. A surplus North American Harward was used – the New Zealand Territorial Air Force version of the T-6 Texan, a ubiquitous WWII-era trainer and light bomber. Pellarini used the pieces of the decommissioned aircraft to construct an improved and updated version of the PL.7. So, if there was ever an airplane which looked like an improperly assembled wreck, it was the PL.11.

Bennett PL-11 Airtruck (Image: Flyernzl / Wikipedia)

In doing so, Pellarini doubled down on PL.7’s weirdness. The new aircraft was a monoplane, with two widely-spaced tail booms. Most importantly, the cockpit was placed on top of the ‘barrel’, which took its toll on the aircraft’s aerodynamics but vastly improved the visibility for the pilot and allowed for a spacious cargo bay.

The bay could house a substantial amount of fertilizer or be a passenger cabin which, if some accounts are to be believed, was roomy enough to fit up to five people.

To emphasize the cargo capacity of the new airplane, a new nickname was selected: the Airtruck. However, the first prototype of the Airtruck crashed in 1963. A few years later the second prototype was completed, only to crash as well. Bennet – by that point reorganized into Waitomo Aircraft – decided to stop pursuing the idea.

Back to Australia

While it seemed that Pellarini’s initiative was over, a new player entered the market. Australia’s Transfield Holdings decided to try where Kingsford Smith had previously failed and build an Australian agricultural aircraft. In 1965, the company established Transavia Corporation. Later the same year, a new and improved version of the PL-11 took off.

It sported a new Continental O-520 engine, which later made its name by powering Beechcraft Bonanza, Bellanca Viking and countless other small aircraft. Getting rid of radial engine improved aerodynamics, and further improvements to the airframe were done as well.

The general configuration of the cockpit above, cargo deck below, and two tail booms behind remained. The aircraft looked arguably less ridiculous than its predecessors, and that may have helped it through the development process.

With the new powerful engine, it could lift almost a ton of cargo while weighing barely more than 750 kilograms, a feat few other aircraft managed to replicate. The name of Airtruck would have fit the vehicle like a glove, but that name was owned by Waitomo. So, Transavia used the name ‘Airtruk’.

Finally, the weird little aircraft was successful. Satisfied with the results of the tests, Transavia arranged for serial production, which ran until the late 1980s. Different sources give the number of Airtruks produced as between 110 and 150, including several improved modifications. Even more variants – including an armed anti-insurgency aircraft proposed by the Royal Thai Air Force – were proposed and never built. A lot of PL-12s were exported, and one heavily modified example was featured in the Mad Max movies.

Weirdly enough, it was Pellarini’s most successful project and the only mass-produced aircraft he designed. Having spent most of his early career trying to convince the world that sleek futuristic flying cars were the way of the future, the Italian designer ended up being immortalized by one of the strangest aircraft of all time.

Upgraded Transavia PL-12 Airtruk T300 at Museo de Aeronáutica y Astronáutica de España (Image: Bidgee / Wikipedia)

Source: Aerotime Hub

Warning: Illegal string offset 'cookies' in /home/u623323914/domains/eng.bayviet.com.vn/public_html/wp-includes/comment-template.php on line 2564